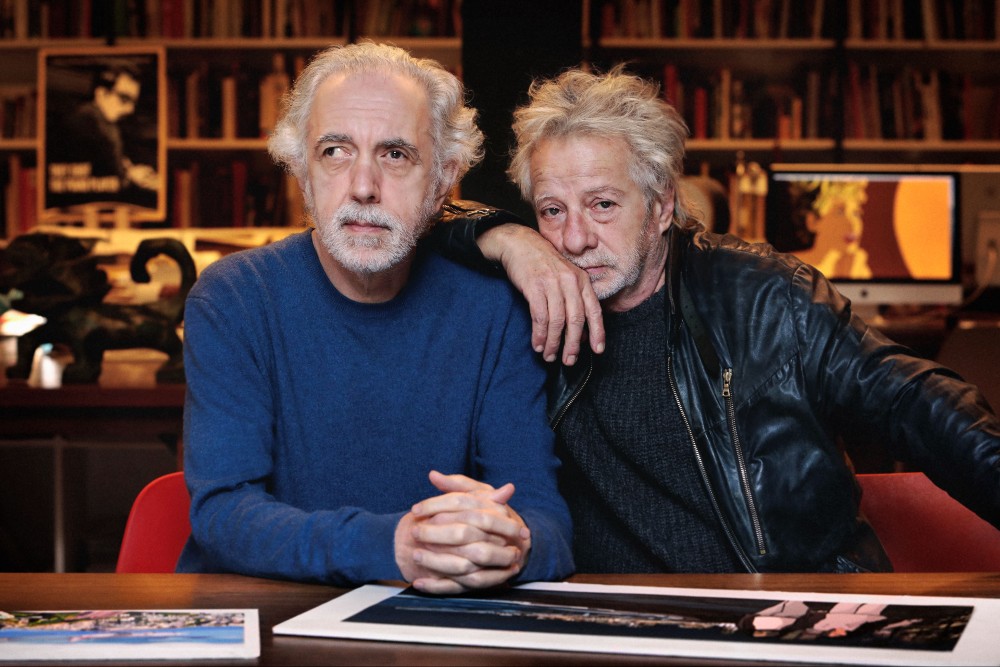

Spanish filmmaker Fernando Trueba has essentially done just about everything one can do in the worlds of music and movies, having directed the Oscar-winning Foreign Language film, Belle Époque, Spain’s Oscar submission, in 1995, and then receiving another Oscar nomination for his animated film, Chico & Rita, in 2010. He also has produced records and has his own Latin jazz label called Calle 54 Records, which has brought him two Grammys and four Latin Grammy Awards.

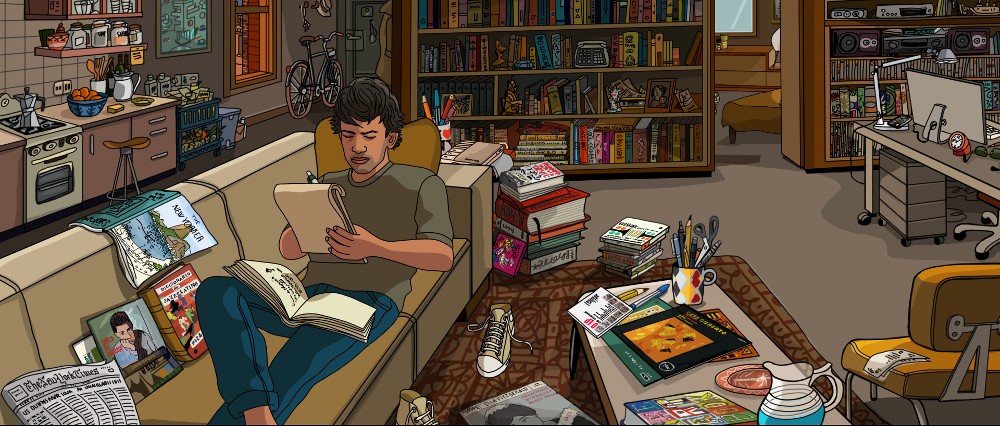

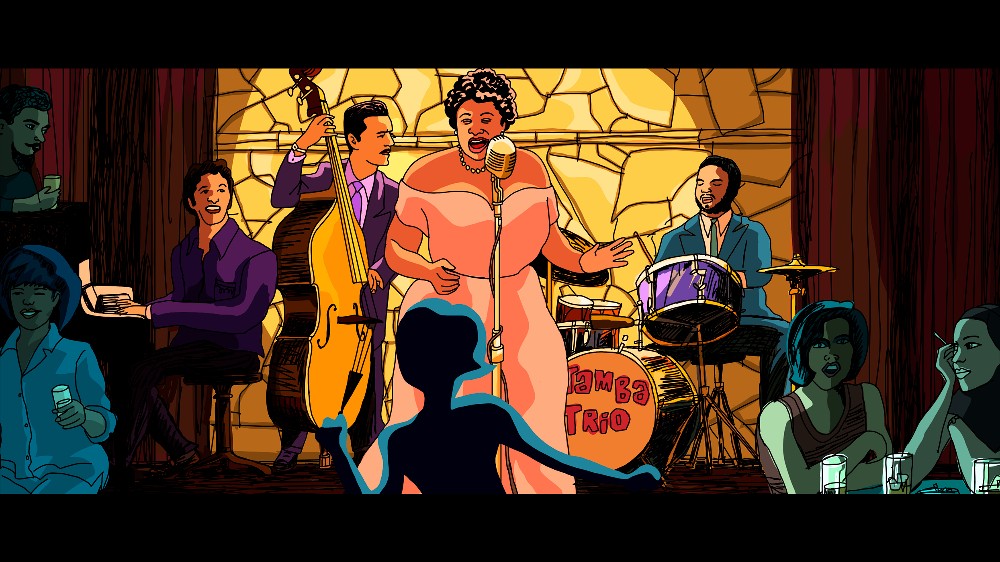

Trueba has now reteamed with artist Javier Mariscal (co-director of Chico and Rita) for They Shot the Piano Player, an animated semi-documentary that explores the South American samba scene through the life and career of accomplished pianist, Tenório Júnior, who vanished in 1976 while in Buenos Aires, Argentina for a gig. The story follows [fictional] music journalist Jeff Harris (as voiced by Jeff Goldblum) as he travels around South America and other parts of the world, interviewing musicians who knew, played with, and admired Tenório and were mystified by his sudden disappearance.

Trueba seems like the perfect filmmaker to tell Tenório’s story, having many connections in the world of music, from producing records and even having his own record label, and collaborating with Mariscal gives They Shot the Piano Player such a distinctive look and feel from other animated films released last year. The film includes excerpts from hundreds of interviews Trueba did with some of the masters of Latin American bosa nova, samba, and jazz, many of whom have since died.

Above the Line spoke with Señor Trueba back in September at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) where They Shot the Piano Player received its North American debut.

Above the Line: Besides Chico and Rita and this, you’ve made quite a few live action movies, you seem to go back and forth, which is pretty interesting to me.

Fernando Trueba: I must confess that animation is a thing that happened. It happened in Chico and Rita, and the origin was the friendship with Mariscal. We’re very good friends, and to do something with him, to collaborate, because even before we were friends, I loved his work and his colors and his drawings. One day, the idea to make a movie together, and we did Chico and Rita. [That] was a big discovery for me. I realized that, for me, movies were fiction, documentary, or somewhere in between. With Chico and Rita, I discovered another window, another idiom, which depends on which stories can be the real one. Before Chico and Rita, I had started working on this one. I had started in a very personal way, [interviewing people] related with Tenório and what happened to him. In 2006, 2007, I did 150 interviews, mostly in Brazil, but also in Argentina, in the States. People who were friends or played with him were living in different places. My initial idea, very vaguely, was to make a documentary. I stopped to work on Chico and Rita and then for a movie called El baile de la Victoria (Victoria’s Dance).

After the experience of Chico and Rita, I was thinking, what I’m gonna do with this? I thought the idea would be to make an animation, because in a documentary, you just do a documentary about a dead guy with people talking? “No, he’s very good, he was a great musician” things like that. But I wanted him to be alive. I wanted people to watch him play, not just being a dead man, but being a musician, being young, watching him recording his first record, for example, those kinds of things. At the beginning, I said, “Are you crazy? Is this because Chico and Rita had you watching things in animation?” I say, “No, no, it’s better if I do it this way.”

It took me a long time to make the decision. It was not just one day to another, even to talk about that. It took me six months to talk to my wife about it, to say, “I haven’t talked to you about this, because I thought it was something that was going to pass, just a temporary thing, but it’s grown on me. I want to do that as an animation.”

ATL: I want to go back a little bit, because seeing the movie without any context or reference, I knew you were involved, as well as Javier, but I wasn’t sure if Jeff Goldblum was voicing a real person who wrote a book or not. There is no Jeff Harris, right?

Trueba: [shakes his head to indicate “no”] Jeff Harris is an alter ego. I thought that it was more real and more believable that this New York journalist, who is there, and by coincidence, he discovers the story of this man and his music. A Spanish film director in Brazil, what the hell is that, discovering this? I thought the other thing was better.

ATL: Do you and Javier share a similar love of music, so when you suggest something like this, he’s just as interested in doing something in that musical world?

Trueba: He very much likes music, and I’m always suggesting things or giving him records or copying records for him, and he enjoys that very much. I’m not a music producer, but I have produced some records, and I created a small label, and Javier designed the art of all of them. That went from 2000 to 2015 or something. Lately, because mostly the [vinyl LP] thing has disappeared completely. I had some Grammys, but it’s something that I like very much. I like the work in the studio with musicians. I like to one day dream about that record, and then call the musicians to propose a record. It’s like making a movie.

ATL: So you heard of this piano player, and you started looking into his disappearance to find out what happened to him? Where do you go and who do you interview first?

Trueba: First, I heard the music, like in the movie. It was 2004 when I discovered him, and there wasn’t almost anything on the internet at that time. The fact that I wanted to know what he was doing now, and he was doing nothing for 55 days at the time. So I said, “What the hell?” What he thinks in the movie is that he must be dead or had an accident, but then, I discovered this strange stuff that he disappeared in Argentina. I started to dig, and the first thing I discovered is that his death was not really investigated in Argentina or Brazil, because of the state of dictatorships at the time. I had to investigate a lot by myself, talking to many people. That’s why I did 150 interviews.

ATL: You already had these musical connections and had worked with some of these musicians?

Trueba: I had very few, but we spoke with a family, with friends of his, and we were making a genealogical tree with all the connections — he played with this one and this one, and then later, with this one and this one. He was in this group, he was on this record, he was with this, with that.

ATL: The fact that there’s not as much about him on the internet in 2004, how else do you research it? Just from doing interviews or do you go to the library to dig up any mentions about him?

Trueba: Interviews, that was the only way. His widow was giving me… “He was very friendly with this one, maybe you should talk with this other one. I can get you the phone of this one who was very friendly with him at the time,” that kind of stuff. Susanna de Moraes, Venicius’ daughter, who is at the beginning of the movie, also helped me a lot, giving me different connections to people. Everyone that I interviewed spoke to me about another one, so it was like, a big net that was being built.

ATL: Did you already know Jeff Goldblum from your time making movies or from the music realm?

Trueba: We did a movie in ’88 and ’89 together, and we’ve stayed friends all the time. What is curious, I thought about him from the very beginning, because I love his voice. I think he’s like a jazz player with his voice, and he’s a jazz player, too, and a good pianist. But the way he uses his voice is very jazzy. You really don’t know how he’s gonna say the next thing. He’s always unexpected, original, and I love that of him. He’s never boring.

The name “Jeff,” it was in the screenplay from the very beginning, even before I spoke to him about it. My hope was, “I wish so much Jeff will play that.” When I told him and sent him the screenplay, he liked it, and he said, “I’ll do it.” When he saw it at the end, he says he loves it, and that he was very proud to be in it.

ATL: Obviously, you were doing these interviews over the years, and you’re working with Javier on Chico. At what point does he switch gears and start thinking about how best to design and animate this after finishing Chico and Rita?

Trueba: We knew that it has to be a very different approach. Chico and Rita has this nostalgic almost classic Hollywood approach, because it’s the ’40s and the ’50s, the ambience of the music. For this, we wanted to be on one hand more realistic, more journalistic, but we have all these flashbacks, all the stories, because this is a movie about memories, too. Pretty early, we said, “Let’s find a different style and texture and animation for every story in the movie.” That was really all these flashbacks that Mariscal, who is not a cinema guy, he called them “clouds.” He called the flashback “clouds,” so we were looking for the style for every cloud in the movie. That was very interesting, visually, creatively for him, and for me, too.

ATL: When you direct a live action movie, you work with a production designer, who helps you find the look of what you want to do and then finds locations or builds what is needed. With this one, it’s all Mariscal. Had you edited the interviews into some sort of screenplay format, or written a full screenplay before he starts designing it?

Trueba: When I decided that I wanted to make it in animation, I said, “Oh, my God, it’s like climbing a mountain again,” because I had to sit in my home, watch all the interviews with pen and paper and taking notes. And then, because I wanted to keep real voices of the interviews, so I had to edit them, because every interview was one hour or sometimes more. Which interviews I’m gonna use and which words and lines and phrases I’m gonna use from everyone in the screenplay, so I had to watch the whole thing again, taking notes for this next step, which was going to be the actual screenplay.

ATL: All the interviews were recorded well enough that you could use the actual voices? And did you have to get clearances from all the people you interviewed?

Trueba: While I was making it, we had to work a lot with the sound. I work with very with some people in Madrid. If I had known from the beginning, obviously, I would have taken special care for it, but I didn’t know, so we have to work a lot with the sound.

ATL: Are most of the people you interviewed still alive?

Trueba: It’s been almost 20 years, and I will say that a lot have died since, a lot. It’s very sad for me, because the last one, João Donato, for me, the greatest pianist in Brazil for many years, and Paulo Mora, people that I really love, not only as musicians. People that I would have loved to spend more time with some of them. Donato and Paulo Mora, they were geniuses. I remember, and I put it in the screenplay. I found a way. I’m a very hedonistic guy, so I try to put the things that I love. For example, we were shooting interviews every day in Rio, and then, I find out then Paulo Mora and João Donato are making a record as a duo in a studio, and they are recording in two days. We stopped our shooting just to be in the studio with them.

I was not thinking to use it in the movie. [It was] just for my pleasure to be there. I remember that the recording [engineer] was very pissed off, because Donato was all the time talking to me, and the guy wanted to work. I was with the sound recording at a table and Donato said, “Come here, sit” and he wanted me to sit by his side when he was recording, so had to be really quiet. I know what [it’s like to record], but that was very tender of him, to want me to sit there.

When I was writing the screenplay, [I wondered how] I could put this into the movie, so I managed to, because I think it was nice that this guy Jeff goes to the studio and see these two greatest of musicians. I had recorded Bebo Valdés, the Cuban pianist, who was a friend of mine, that I produced eight or nine records with him now, and he’s dead. I remember that when I was doing the research, and I had found some charts of Tenório, I asked him in Madrid, “What do you think of this music?” He said, “I think it’s nice. Let me take it home,” and two days later, he said, “I wrote this arrangement of this song, because I think it’s very beautiful.” I told him, “Let’s go to a recording studio, and we’ll record it.” Not knowing for what, maybe for one of his records. While I was writing the screenplay, I remember I had this song of Tenório, written by Bebo. Bebo was dead by the time, but wouldn’t it be great to hear Bebo Valdés, one of the masters of Cuban music, playing Tenório’s music. It would be something. One of the times Jeff comes back to New York, he goes with his publisher Jessica to the Village Vanguard. Already, a few years ago, I had made a record with Bebo live at the Village Vanguard.

ATL: So you changed things around to fit Bebo into the story you were telling?

Trueba: I was very proud of it. For me, it was like giving life [back] to Bebo for a moment, like [with] Tenório.

ATL: You did all these interviews, spending an hour or more talking to these musicians, so were a lot of the conversations about Tenorio or were you talking about other things as well?

Trueba: Obviously, with some of them, like Carmen or Molina, I did more than maybe three hours. I did two interviews with every one of them, but mostly with the musicians, or the people related to the music, I spent the first part talking about Tenório and the second part talking about the Brazilian music at that time. Not about the political or historical times, more about the years of bossa nova and Brazilian jazz, samba jazz, and all this.

ATL: So you might have a second movie you can make from those interviews?

Trueba: If someone has the passion, they can make a documentary on that with the material I have. Obviously, they can do it, but I put some of it into the movie, but there is too much.

ATL: It seems like there would be a lot of stuff in those interviews that would be of interest, especially with those musicians that had passed away, that people would love to hear. Even if someone wants to transcribe them and put them into a book.

Trueba: I thought about making a book, but I’m pretty exhausted after the movie and everything, and to start again and make a book. I thought about it for many years, but now I want to make other different things also. Maybe one day I’ll do it.

ATL: As a filmmaker and a record producer used to working with different artists, including actors, how do you work with Mariscal? Does he do a lot of work on his own and then come back to you to show you what he’s been doing, and you go from there?

Trueba: He doesn’t do that. He’s like a possessive lover. He wants me to go all the time to Barcelona, because he’s in Barcelona, and I’m in Madrid. I spend my life on the train going to Barcelona, when I work with him, and every time I’m there, he doesn’t let me go to the hotel. He has the room of his son, who is now grown up, and he puts me there in his home, because he wants to spend the whole day working and talking and then the dinner, talking about how we’re going to do this scene, because he’s very talkative about everything, every detail, a bit obsessive. I’m not. I’m obsessive too with the things that I like, but when I work, I try to be very free. But we have very good relationship, very good friends, even if he gets angry with me many times, because he says I’m too rigid. I don’t want to change the script. He calls me “The Taliban” or “Tali,” and I say, “You’re an idiot, because I always listen to your suggestions. I change this and this and this after talking to you, because I thought that was a good idea.” But I have to take care of the movie, and I have to respect the story and the screenplay and some things. Because he’s a hippie, he’s a crazy guy, he’s like, “What if they fly in the room like in a Chagall movie?” I say, “I love Chagall, but… ”

ATL: You’ve done two animated movies now, so do you feel like you’re going to continue in this direction? I guess you have a lot of options.

Trueba: Not for the moment. I never thought I was going to do animation. We did Chico and Rita just for the friendship of being together, and I like his drawings of Havana, so that inspired me. Now, I had this story, and I decided to turn it into an animation. If you asked me, “Do you think you’ll do more?” Maybe not, because it’s too long, and it’s very expensive. Maybe if I had an American producer, and we have more money, and it makes our life easier to make it, because it’s a lot of sacrifice, to make these kinds of movies, for us, as Europeans. We are not Disney or Pixar or something, but if we had this kind of production, imagine that tomorrow, an American producer says, “I want to produce your next thing, and you will have a normal budget” — I’m not asking for the moon just a normal thing — maybe, but if not, I think it’s like trying to win the war with a bunch of friends.

ATL: Has anyone ever done a retrospective of your films in New York. I assume they must have in Spain, but I was looking over your list of films, and you have all these different things beyond Chico and Rita and Belle Époque, so I wondered if Film Forum or Lincoln Center had ever approached you about doing one.

Trueba: When one of my movies opened in New York some years ago, they did a mini-retrospective of five movies at the Quad. Before Memories of My Father – it’s called Forgotten We’ll Be – they did a retrospective of maybe five of my movies the week before, but you can call this a retrospective in the way you mean. I don’t know.

ATL: You don’t want to have people see your movies that might not screen as much?

Trueba: I always got pissed off when I saw that there was a new book on a young director, and the guy has made two movies. I’ve seen that several times in America, and in Spain. I always thought the first book on John Ford, he had already made 130 movies when they wrote the first book on him. I’ve done one thing in Spain. I had boycotted any project of making a book on me. Some friends and people close to me get angry with me. “Why don’t let them do it?” I let them; I can’t forbid it, but I try to convince them not to do it. Do another thing, I’m always convincing them. You can say it’s modesty. No, I think it’s fair.

I remember William Goldman, the screenwriter, in one of his funny books, maybe Adventures in Screenplay, or he said one thing. He said, “Hitchcock was the best director until the French critics wrote he was a genius,” talking about the Truffaut book, which is a master book. You say it’s cruel and fun and maybe it’s true. He was making the greatest movies in American cinema, or maybe it was just a time coincidence, because he was old, maybe he was drinking too much, but it’s true that after The Birds, he never did that great movie again. So when you’re making movies, the less you think about yourself, the better. The less you think about your work, your oeuvre, the better. Just make movies. Try to make them as good as possible, because if you are watching yourself in the mirror, in a narcissistic way, it’s gonna affect your movies. Sometimes it’s better if you are underrated. The problem is the opposite. Underrated is not going to hurt you; overrated yes, because human beings, we have the tendency to believe the good things they say about us…. and that’s dangerous. [chuckles]

ATL: Sure, but maybe you might want to do a book or retrospective for the other people who love your movies and want to learn and know more about you, so your work will be remembered.

Trueba: I love that people like my movies. Obviously, I do it for them. When I’m in the street and people approach me to say, “Oh, I love that movie.” I’m happy, obviously.

They Shot the Piano Player will be released into select theaters on Friday, Feb. 23.