Illeana Douglas is a wonderful actress who has appeared in over a hundred films including several classics like GoodFellas, Cape Fear, Quiz Show, To Die For, Grace of My Heart, and Ghost World. In recent years Douglas has gotten involved with film history, writing and podcasting for Trailers from Hell, and doing segments for the beloved cable channel TCM. She wrote the excellent and funny book I Blame Dennis Hopper a few years back.

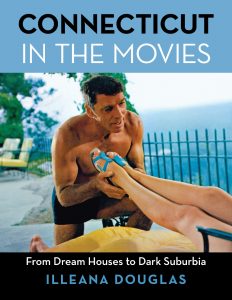

Recently, she relocated back to Connecticut which in turn inspired her new must-read book, Connecticut in the Movies, in which you will learn a lot about the state and its indelible movie lineage. It stands out as the first major book on this topic whereas there are hundreds of books about films set in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, to name a few. Beautifully designed not to be a light read but an immersive experience into the cinematic journey of a state that has a rich history from Katherine Hepburn to Paul Newman, Douglas’ book covers gems like the cult classic The Swimmer and forgotten 80’s gems like Stanley & Iris, Jacknife, and Julia Roberts‘ storied debut Mystic Pizza. Above the Line recently caught up with Douglas, the conversation has been edited for clarity.

Above the Line: What inspired you to write this book?

Ileana Douglas: It was something that the idea of Connecticut cinema, because I grew up here, always sort of fascinated me and the fact that nobody had ever kind of acknowledged the fact that Connecticut was always being used as kind of an unseen character. In many, many films I would hear a character was from Connecticut or they were on their way to Connecticut, or of course, the Stepford Wives is placed in Connecticut. And so that idea always percolated with me.

ATL: You speak fondly of some unfairly overlooked films, and one of the standouts is Stanley & Iris; please elaborate.

Douglas: There are a lot of important issues that are being spoken about in the movie, and then it’s also a love story. I think it’s a beautiful film. I spoke to Jane Fonda about it, because I’ve interviewed her a couple of times, and she looks back on making the movie very fondly again. It was sort of an experiment. That’s when Hollywood stars like Jane Fonda would be in a movie with a gritty, realistic actor like Robert De Niro. It’s got a lot going for it. And I love their chemistry in the film.

ATL: Tell us how you ended up relocating to Connecticut.

Douglas: I wrote about this film that I had always really liked, but I thought had been thrown to the wayside, Stanley and Iris. After I finished writing about Stanley and Iris what I always try to do with films is take a different approach to the film. I don’t approach it from a movie theory or what the reviews were; I like to just look at it with kind of fresh eyes. I saw it now through the lens of Waterbury and the rise because, within Connecticut, Waterbury was kind of like a little New York. It was this thriving metropolis, and I wrote about it from that point of view.

That’s when I thought, “Well, maybe there’s a book in here in which you could talk about the history of Connecticut through these different films.” There’d never been any kind of a guidebook that was an incentive to explore Connecticut through films, so that seemed like a very appealing idea to me. The unexpected part of writing the book was that halfway through the book, I started scrolling it through Zillow and thinking I wanted to move back to Connecticut and restore an old farmhouse, which is a plot ripped from many of the movies I was writing about. The other thing that’s incredibly important about the film is that we don’t make movies anymore about the working man. That was director Martin Ritt’s bread and butter, what he called the “Dignity of the Working Man,” and Waterbury, as I learned, was built on the backs of immigrants who worked in factories, who built Waterbury, the clock factories, the brass factories. I found it to be fascinating, just thousands of immigrants of all stripes worked in these factories that lived in, what they call “triple-decker houses,” meaning families on each level of the house. You can see that in the architecture of the film, and I’m fascinated by architecture in houses anyway, and so, the movie speaks to the working man and the blue-collar worker.

Douglas: It’s a terrific under-seen film about… it’s not about the guys suffering. I mean, we just sort of stopped talking about people suffering from PTSD. We just don’t talk about it anymore, as if we solved that problem, and that’s what the whole film is about, and how the one character, Robert De Niro, is finding a little bit of joy from fly fishing. That’s where, again, Connecticut – really, the town of Marin – plays a part in that film and that background. People that go to diners and just… I guess we’re so afraid to show people in everyday environments, maybe we think that they won’t relate or that they will think it’s boring or something.

ATL: We must talk about Katherine Hepburn, because she is such an important figure in the history of Connecticut film.

Douglas: Katherine Hepburn is not only an ambassador of Connecticut, but she is sort of the brand. She delivers the brand of what Connecticut is. She’s an authentic personality. Her family was part of a group of Bohemians – they were wealthy, but she lived a kind of bohemian childhood. They had a house. It sort of is the Connecticut lifestyle. And when she does this movie Bringing Up Baby, you have her full Connecticut brand on display. She’s got this kind of wild, unruly hair. She’s wearing pants. She is pursuing Cary Grant. She is sporty, she plays golf, then she has the wacky family living in Connecticut. What was interesting about all of this was that, although she was being her authentic self, the studio hated it, and they hated her in the film. That was kind of her career-ender, and then she goes back to New York and Broadway and buys The Philadelphia Story and then comes back triumphantly.

ATL: How did you find the DIY house from Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House?

ATL: How did you find the DIY house from Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House?

Douglas: That is something, again, that I had known about what I wanted to put together in an impactful way that the film was out of all the films. It, again, carries this idea that living in Connecticut is superior to living. The phrase that they use in the movie is, “Come to peaceful Connecticut. You can have the dream house you always wanted.” This replicates real author Eric Hodgens, who was living in New Milford, Connecticut. New Milford, Lichfield County, at the time, was where all of these New York executives, artists, writers, et cetera, were living. And then, he writes about his experience of building a house and it goes haywire, and he goes bankrupt, and he ends up losing his house, and he wrote a book about it. But the movie took it one step further. This guy named Paul McNamara, who was the publicity man, decides it would be fun to sell kid houses of the Blandings House, so you have the Blandings House in the movie, which is a replica of a Connecticut house. And then now you have these kid houses which are sold all over America, which are the essence of what we think of when we think of the “perfect house,” a white clapper house with green shutters. Now, back in the day, you could get your kid a house, and you could have add-ons like a bomb shelter.

ATL: Please tell us about the cover, it is a striking image and it is from one of the most quintessential Connecticut films, The Swimmer.

Douglas: I am very proud of designing the cover. When I was writing the book, this was always the image I always imagined, and the blue colors reflect what used to be the license plate of Connecticut. So I wanted that kind of a resting image for the cover, because again, it says a lot. “Dream houses to dark suburbia” – it’s all within that one image.

ATL: What was your first impression of The Swimmer?

Douglas: I worked on a movie with director Frank Perry, and he gave me a copy of the film. It was the first movie that I ever saw that specifically talked about the culture of Connecticut in many different ways. The class system is the kind of what I call misplaced values of wealth status. I always loved the movie, and it’s grown in popularity over the years as kind of a cult film, even though it was a big failure when it came out. I did an essay for Trailers from Hell, and people enjoyed the essay, then I thought about writing a more expanded essay on Connecticut films.

ATL: Another iconic Connecticut movie is The Stepford Wives.

Douglas: It’s interesting, because the book is probably better than the movie, where they got it wrong because they made the women look more like Playboy bunnies, and they added a sort of a California spin on it. They didn’t capture what they were trying to say in the movie, that it was all about conformity and everybody looking alike and being alike and following the rules and everything perfect is not so perfect. The movie goes a little bit awry, because it turns into this battle of the sexes, which I think was going on at the time, so they infused the movie with a lot of that, and that, to me, is what is not so successful. But what it successfully did was that from that moment on, whenever you have a movie now set in Connecticut, you’re hinting to the audience that something horrible is going to happen.

ATL: Obviously, another iconic movie from the eighties is Mystic Pizza. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Douglas: I wanted to focus on the story of Amy Holden Jones, who wrote the script, but because of the time, [she] was not allowed to direct the film. She accidentally landed in Mystic with her husband Michael Chapman, the director of photography, and they had stopped to look for Fried Clams when she saw the sign “Mystic Pizza.” Because of her background working with Roger Corman, who said to come up with a title and then come up with a movie, she saw the “Mystic Pizza” sign and said, “That would be a great idea for a movie.” She had just recently seen the film Diner and wanted to do kind of a female version of Diner, which is a great premise for the movie. And so then the script, she ended up moving to Mystic and writing the whole script. So it has the flavor. All three girls in the film, you believe they are from Mystic, and again, it’s a movie that talks about the class system. I think it showed the limited choices that you have when you don’t have a lot of money and you’re living in a state where some people have a lot of money. For me, that’s what is so important about the film. I had never seen a movie before where the rich people and the townies are occupying the same bar. We don’t get movies like that blatantly.

BTL: We haven’t mentioned Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward, both very Connecticut people.

Douglas: They did two important independent films here, but I specifically write about Rachel, Rachel, because again, you have someone that is not only an ambassador for Connecticut who’s living here in the state, who starts a charity that’s based in the state, the “Hole in The Wall Gang,” which is this incredible camp for sick kids so they can go play. They work at the Westport Playhouse, they support the Westport Playhouse, and they’re responsible for bringing other people into the area, because of the very idea that they were there. Then it brings in other people like Robert Redford, other people getting houses in Westport. But the movie Rachel, Rachel, it’s an independent film entirely made in Connecticut, and nobody talks about it beyond it being a Joanne Woodward movie.

ATL: One movie we didn’t mention is also probably one of the only more modern movies, The Ice Storm.

Douglas: But in The Ice Storm, we have the added, which I think is a modern spin opinion. The parents have to be punished for their actions, so there must be retribution for all this pill-taking and drinking and wife-swapping. A child must die for the parents to look at in the mirror and see that the way they’re living is wrong, and I just find that interesting. All of the movies in dark suburbia redux have a modern point of view about the past. Now, that’s something I stumbled on accidentally, as I was writing about these movies because all of the movies about the past “revolutionary road” are again, graphically sad. It’s like suburbia equals death. It’s worse than The Stepford Wives. The sixties or the late fifties into the sixties, but they’re all incredibly artful. They’re more art. As I said, people are walking around in these incredible houses. Every single film has someone looking out a large picture window with trees reflected on them. Isolation, the loneliness of suburbia, retribution for living here, somebody has to die in one of these films.

ATL: Will we get a return to dream suburbia?

Douglas: I don’t know. Well, that’s what I write about in the book is currently “dream suburbia” is this cotton candy hallmark movie, where Christmas in Connecticut is on steroids.

Connecticut in the Movies: From Dreamhouses to Dark Suburbia is now available at all good book sellers, including Amazon.