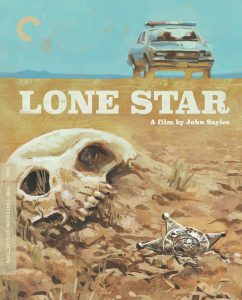

Being entered into the vaunted Criterion Collection is tantamount to a movie being knighted, and few films from the 1990’s deserve that honor more than writer/director John Sayles‘ neo-western Lone Star. The Texas-set tale features a Godfather II-type structure where a young border town sheriff (Chris Cooper) slowly unravels the story -via flashbacks- about his father (Matthew McConaughey), who was a legendary sheriff in the community during the 1960’s. This search for the truth is kicked off by the discovery of the long-dead remains of a particularly nasty racist sheriff (Kris Kristofferson), who was at odds with McConaughey’s character.

The new Criterion Blu-ray of Lone Star features a 4K re-master along with a new interview with Sayles and several other features, along with a liner notes essay by Domino Renee Perez. A re-watch of the film reveals old pleasures in its complexity along with startling parallels to today’s issues, all of which Above the Line discussed with Sayles (Matewan, Eight Men Out) when we had the chance to speak with him 1:1 recently about the film.

Above the Line: So many of the social aspects of the film, like the debate about teaching real history in school, border politics, how police figure in black communities… it all still feels very contemporary.

John Sayles: I’m afraid that’s kind of sad that we haven’t solved any of these problems, for sure. Some of them are even worse. Certainly the battlefield of how history is taught, is really raging now, and it was already pretty bad when we made the movie.

ATL: In 1996, did you think we’d still be wrestling with these issues in 2024, to the point where it seems almost no progress has been made?

Sayles: This is a long, long story, but I have seen progress. I go down South a lot and I don’t see that flag the way that I used to. Some of it is just a generation dying off. Someone from the next generation said, “Well, they’ll be a pain in the ass, but okay, what the hell, it’s more trouble than it’s worth now.” It’s just not as important to them. In our country, until the late 30’s, we had two celebrations of our veterans. There was Veterans Day, and in the south black people would go to the cemetery where the Union soldiers were buried. Then there was the day of the Confederate dead, and that was a week earlier or later. We didn’t even celebrate the same thing until pretty late in the game. Things do change, but it’s not like, “Oh, the scales have fallen from my eyes!” It’s just, “Well, granddad’s dead, now we don’t have to keep the flag up.”

ATL: Kris Kristofferson was such a counterculture hero. He was Billy the Kid. His song “Best of All Possible Worlds” is railing against the very kind of crooked sheriff he’s playing in this movie. Was that casting against type deliberate for you?

Sayles: I got interested in, “Who are the Texan actors?” And I thought, “Well, Kris Kristofferson is from down around Brownsville… he’d know these people.” I’d never seen him play a really bad guy before, but he had that kind of presence and that voice. I thought, “Well, that would be interesting.” He always joked that, “Oh, yeah. When my wife read it, she said, ‘Finally, you’ve been typecast.'” But he understood the part, and was willing to throw himself into it. Certainly, because I listened to country music, I knew him as a songwriter first. He’s not a bad performer. He’s got a lot of charisma. He just kind of started being in movies and it was like, “What a refreshing guy to have in the movies.” He had another life. He was an Army guy before he even became a songwriter.

ATL: I think he’s actually said in interviews that Lone Star changed his career trajectory, because people hadn’t thought of him for these antagonistic roles. Do you think he was, in essence, channeling a lot of the things he hated about authority into this figure?

Sayles: I think so. He was a little older than me. He grew up on the border, understood those rules. I remember going to the south when I was a kid and being blown away that African American men would take their hats off when they talked to white people, even people half their age. That was just the rules, and nobody said anything about it. It was like, “Jesus Christ.” I remember being in the train station in Washington DC and getting yelled at as a little kid because I wanted to drink the colored water. I thought it was going to be blue or red or something. “That’s not for you, boy.” He probably had, being who Kris was, a real animus about those kinds of rules of engagement in communities. He said he was a big fan of border music, of Mexican music and that kind of Roy Orbison mix of Tejano music.

ATL: Lone Star presaged a lot of the Cormac McCarthy neo-westerns we got onscreen years later, but his books existed at the time you made it. Was he an influence?

Sayles: I had read Blood Meridian, and really liked it. I think that’s the only one I had read at that time, but it’s such a brutal book. A lot of people have said, “We’re gonna make that movie,” and it’s never gotten made. I don’t know if it ever will. It’s more that I read Westerns when I was a kid and my favorite ones were by Elmore Leonard, and a bunch of them got made into movies later on. There was a part of Elmore Leonard that was, “Okay, I’m gonna make a real Western and there’s going to be those confrontations that are kind of iconic, but I’m also going to talk a little bit about the politics of the place.” So often the bad guy is the government agent who’s stolen from the Apaches at the San Carlos agency. That’s why he’s in the stagecoach that the bad guys want to get. So there’s a bad guy in the stagecoach, as well as the bad guys that want to get the stuff. The western genre and the west was always interesting to me, but I also knew quite a bit about the guerrilla war that lasted a long time between the Mexican community and the Texas Rangers. The Texas Rangers were totally Anglo, and they pretty much would get into these wars with Mexican people who still owned a lot of land and helped take it away from them, not always in a legal way. That kind of battle was in my head when I decided to make the movie.

ATL: Most people outside the business wouldn’t even know his name, but your executive producer John Sloss has been a huge force in independent film. How important was he in the 90’s era of your career?

Sayles: Yes, John Sloss was an assistant to the first lawyer that we had when we made Lianna and Matewan. Then he became pretty much the guy who was doing law for people who were making independent movies on the East Coast, and intellectual property law and dealing with these companies that might exist one year and not the next. It was kind of a specialty, there wasn’t that much money in it, but he liked being a player in that world.

ATL: Companies like Shooting Gallery and such.

Sayles: Yeah, and then he eventually had his own company that never had that much success of raising money for movies, but he was willing to talk to Harvey Weinstein, deal with some pretty impossible people, and then some people who were more reasonable, but it was a very small field on the East Coast. It was a different thing going on out here in the West Coast.

ATL: The late Elizabeth Peña was always a warm, vibrant presence on screen when I was growing up, and she’s so incredible in this film. What do you remember most fondly about her, because you worked with her quite a bit?

Sayles: She was just fun. She was in a TV series I had written called Shannon’s Deal, and had a big part in that. I met her during that, and I had seen her in some early indie movies where she mostly spoke Spanish. She could do the heavy dramatic stuff and she could do comedy at the same time. There was a TV show, I don’t know if it lasted more than an episode or two, that was gonna be a play on I Love Lucy [I Married Dora]. I don’t think it lasted more than a couple episodes or something like that. She was one of those people you just noticed when she was in a movie. When I came to do this, I said, “Oh, this is going to be a major character. We’ve really got to be rooting for her emotionally in this thing.” I thought of Elizabeth right away, because she was a really good emotional actor.

ATL: You do a great Q&A with director Gregory Nava on the Criterion disc, and you mentioned how you and the studios had kind of a mutual disenchantment with each other in terms of the stories you wanted to tell. I don’t know if you took Lone Star to studios, but do you think the twist at the end was or would have been the biggest sticking point?

Sayles: I think generally studios have something in their head where this either clicks and it looks like it could make money or it doesn’t. This is a complex story. Many of them wouldn’t have gotten to the end of the screenplay, because they have stacks of scripts on their desks, all of them. Development people read them first, but even pretty far up the ladder they have to read a lot of scripts and they don’t finish them all. In fact, they don’t finish that many of them. I would say that it would be more that complexity of the world. “Is a broad audience going to want this thing?” Generally it’s like, “Well, it’s kind of in the West, and people really want to know who the white hats and the black hats are… Yeah, this is much too gray.” We don’t even know how we feel about things until the very end, and even then there’s a couple of ways you can feel about it. I think that’s usually why our stuff is usually, “Jeez,I like this but it’s not for us.” This is what we get a lot. Sometimes they have read the whole thing, but it’s just like, “This may be a little too complicated for a general audience.” That’s what we make.

ATL: When Paul Shrader was making Mishima, he said he was in the fortunate position of making a film where the people financing it knew it wasn’t going to make money. He’s probably been in that position many times in his career, as have you, but Lone Star really did pop and find an audience. Why this one and not some of your others, especially because so many of your typical cross-cultural elements are still there?

Sayles: The iconic things of the badge and the hat and the boots was a comfortable thing for audiences, but also Castle Rock. They decided to make the movie, they didn’t tell us, “Oh, you’ve got to hire much more famous actors to make it.” They liked the movie, and they put more money into and pushed the distributor harder than has ever happened on any of my movies before. There was an effort there. Very often we’ve handed a movie over and they just stick it into the system, to the usual suspects. “Here are the theaters that play our kind of movie, and we’ll see how it does.” Then we’ve had people where it gets one review that isn’t good in the wrong journal, and they say, “Oh, well, we’re not going to throw any more money at this thing.” They give up on it two days after it opens. It is a business. This one had the advantage of a company that said, “We’re going to make this work,” and then put their money where their mouth was. Then I think it was the title Lone Star. There is a Clark Gable Western called Lone Star that sometimes people bring the wrong DVD or whatever. We get a panic call. “Do you have some version of this that we can show at our festival, because we advertised it?”

The new Criterion Blu-ray edition of John Sayles’ Lone Star is now available at home video retailers everywhere.