You may recognize Justin Chon as an actor from the Twilight movies — or perhaps the comedy 21 & Over or the crime flick Revenge of the Green Dragons — but for nearly a decade, Chon has also been directing feature films, becoming a trailblazer of sorts in the realm of Asian-American cinema.

Chon broke out with his 2017 indie Gook and earned further acclaim for its follow-up, the 2021 drama Blue Bayou, which paired him with Alicia Vikander. He also recently directed four episodes of Pachinko for Apple TV+.

Chon’s latest film, Jamojaya, premiered earlier this year at the Sundance Film Festival, where our own Editor-in-Chief Jeff Sneider called it “the best of the fest.” The film stars real-life rapper Rich Brian as an up-and-coming Indonesian rapper whose father (played by Yayu A.W. Unru) has been his manager throughout his entire career, though his position is threatened by the rapper’s new record label, which seeks to replace him with someone more experience.

It’s an emotional film, to say the least, filled with both heart and humor, as well as hope and regret. Watching Jamojaya may even prompt you to call your own father after. The movie is also still available for distribution as far as we know, and we strongly urge the industry’s smart acquisition executives to take a close look at this film, which deserves to be seen.

Above the Line spoke to Chon several months ago about Jamojaya and his previous films, and he also offered up some details about what to expect from his new Apple TV+ series Chief of War, which he’s been busy filming in New Zealand with star Jason Momoa.

[Note: The following interview was conducted in February 2023, long before the Writers Strike.]

Above the Line: Growing up as a Korean-American, I rarely saw myself reflected on the big screen, and then when Parasite won Best Picture and all of those Oscars, it was like, “Oh, we’re finally being recognized for something.” You’re also someone I see as a leader as far as Korean representation goes, but I’m curious if you see yourself as one…

Justin Chon: No [laughs], I’m just doing the work I feel like I’m supposed to do. Something like Parasite, that’s “Korean-Korean,” you know, that’s not really Korean-American or Asian-American. I think that’s more international cinema as you would look at Iranian cinema or something. I do think there is a bit of separation because we [Asian-Americans] have such a different experience in this country than living in a homogeneous society like Taiwan or Korea or Japan or something.

ATL: You just pointed out that Parasite is, as you said, a “Korean-Korean” film, not an Asian-American film. Are there any films or filmmakers that inspired you that you think have a similar Asian-American feel?

Chon: I do wanna say that Parasite and Bong Joon-ho [and] Kim Jee-woon, all those guys inspire me to no end. I’m just making the demarcation and the differentiation of Asian-American cinema and how we’re viewed in this country. With an Asian director from Asia, for example, [like] Wong Kar-Wai or Hou Hsiao-Hsien from Taiwan, when you think about it that way, their experience has been completely different in terms of where they grew up — in a homogeneous society where everybody looks like them. Their films are incredible, it’s just a different perspective.

And when we talk about Asian-American films or films that help mold [the] opinions and ideas of people around us in the United States, or even in Europe, like when someone sees Blue Bayou as opposed to Parasite, they’re looking at an Asian person that has had an American experience, not someone [who’s] in Asia. I just want to clear that up.

But in terms of Asian-American [films], I mean, a mentor of mine is Wayne Wang. He’s the OG of indie Asian-American Cinema [with] Chan Is Missing and he was a trailblazer and a lot of people don’t give enough credit to him for his existence, you know? He did Smoke with Harvey Keitel and he’s just been around, and now he’s on the Criterion Channel. He’s getting a lot older and he’s basically retired, but I really love him. I mean, in the ’90s, anything that came out would be, like, a big deal for me, like Chris Chan Lee with Yellow and Better Luck Tomorrow with Justin Lin. All those, I think, at least had some sort of impact in the sense that Asian-American filmmaking existed at all.

[Those were] influential as an Asian-American. Now, as a filmmaker, it’s completely different. I have such a wide range of directors [who] have influenced me, from Asghar Farnadi to Hirokazu Kore-eda to even, I don’t know, someone like Michael Bay [laughs] and James Cameron. I mean, that’s just classic American storytelling, and we’ve seen how much people have been yearning for that with Avatar [The Way of Water] — he just makes classic sort of universal films that everybody can kind of relate to.

ATL: I read that you actually went to Korea when you were in college, is that correct?

Chon: Yeah, I spent a year there.

ATL: I was adopted from Korea, but I haven’t been back since I was six months old, so what would be the first thing you’d recommend for a first-time visitor?

Chon: Ooh… I think the first thing I’d recommend is [to] stay away from any expat community — just get into it. And then I would spend a few days in Seoul, but what I’d say is, [you should] really try to travel outside of Seoul because you can really get by just being in the city, [but] I think when you get out into the countryside and stuff, I feel like you get much more of an immersive experience rather than a city experience because being in Seoul, I think it’s really wonderful, but you could have a similar experience being in any major city like [in] Japan or Taiwan or something. Being out in the sticks, I think it would be quite shocking, but also really fun.

ATL: Would you ever consider doing a film in Korea?

Chon: Yes, I’d be open to anything, [but] the story has gotta be right and I just haven’t found anything that I feel that passionate about. I mean, [for] Pachinko, I was in Korea for a while shooting that — and I consider those little films. I mean, not “little” — they’re films — [but] each one of those scripts on the page was, like, 75 pages an episode, and then we had to cut ’em down to 60 minutes.

So I feel like during that time, it was really great for me, actually. I thought it was sort of good training to stretch myself in the studio system. But I, essentially, made four films during that time, and shooting [in] Korea was beautiful [and] wonderful, so it’s not that I haven’t done it, but I do think it would need to be right if I was gonna spend a lot of time writing something and setting up shop there. But I’d love to shoot everywhere. I mean, I’d love to shoot in Europe, I’d love to shoot in the South again, I’d love to shoot in New York and other countries, [too]. But I guess, for me, it comes down to [the] story and the script… I don’t know.

I think this is the most in-depth interview I’ve done for Jamojaya. At Sundance, it was just like those roundtables and doing like 5-10 minute interviews, but if I’m getting into it, I don’t think I’ve said this, but I think Jamojaya might be, maybe not the last — I’m not gonna say I’ll never do it again — but I’m starting to shy away from the experimental and do stories [that are] not as small-budgeted.

There’s a certain type of movie you can only make with that kind of a budget, and I’m starting to want to tell stories that, even on the page, can be a little bit more accessible to more people rather than me trying to convince everybody — because I will say [that] with Jamojaya, it’s hard to get people to really understand that it is universal with the father and son. And The Farewell and those kinds of films are, like, winning the lottery, still.

I’m looking at the films right now at Sundance and all the ones that went there independently, none of them got sold at the festival. We’ll see what happens now, but none of them got sold out of the festival. And a question people will probably ask me is, “What do you think the state of Asian-American cinema is?” Or, “Where are we going?” Well, you don’t need to ask me. You can just see the state of commerce because [what] people put dollars in is what they feel is commercial, profitable [and] worthy of financial resources.

We went through this weird sort of thing where we had Crazy Rich Asians and The Farewell and a few Asian-American films, and I don’t know if COVID had anything to do with it, but people have these films that are Asian-American centric, but unless you have a really high concept, like Everything Everywhere All at Once right now, I think it’d be hard, maybe, for The Farewell to do the same thing now post-COVID that it did pre-COVID, in my opinion.

And when it comes to where I wanna shoot and what I want to do, I think it’s Asian-American no matter what, just [due to] the fact that I’m directing it. Even [for] you as an adoptee, it’d be Asian-American because of your experience in this country.

So I don’t know. I’ve done five films — I did one film before Gook called Man Up and it was a stoner comedy with two Asian-American kids growing up in Hawaii, and then there’s Gook, there’s Miss Purple, there’s Blue Bayou and then now there’s Jamojaya — and that’s now been the last 7-8 years of my life. If you include Man Up, it’s about 10 years now. So I’ve been directing 10 years [of[ strictly Asian-American films, and I think it’s the end of a cycle for me. I’m still doing Asian-American — just maybe in a different kind of way than [with an] under $5 million [budget] because frankly, I don’t even know [that] people appreciate [indie films].

It’s, like, funny because I remember Blue Bayou [and] I read some reviews and they didn’t feel like the Vietnamese storyline was necessary. And when I looked at their race, they’re all white people that said that. They said [they] didn’t feel it was [necessary]. Well, that’s because you don’t [understand].

You saw the film. I mean, he (Antonio LeBlanc, Chon’s character) never had an Asian mother, so that was a surrogate Asian mother [who] was a mentor figure and helping him cross over. So there was a dual death; there was a physical death — it was metaphoric — [but] it was a physical death, which is showed by her, [and] there’s the death of identity as an American. But when these people watch these films, I don’t think they’re really looking at it that deeply or caring to [look], so they just flippantly say, “You know what? That Vietnamese storyline is really unnecessary. It’s erroneous.” Well, then you’re saying our experience is unnecessary because the whole fucking point of the fucking film is to talk about our experience.

And what I feel right now is that I think they [critics] care if we present it in this, like, really palatable [way], but the flip side of that is, maybe I didn’t do a good enough job conveying why that storyline was in the film. I thought it was pretty clear, but maybe I’m not doing a good enough job because I do need to help everyone understand what it is I’m trying to do.

I put so much damn time into these films; even Jamojaya was like a five-year process. I haven’t read any reviews because I learned not to after Blue Bayou because out of Cannes, it was just terrible. I mean, they were saying it was melodramatic and I think out of Cannes we had, like, a 50 percent rating, and I was like, “Really? It really warrants a 50 percent?”

I gotta make the films for myself. Just hearing from other people what people are saying about Jamojaya, audiences are connecting, I feel. But then the critics just, like, really bash it and just talk about things that are just not the point of the film. They’re trying to look at it as a film where you’re supposed to be entertained, and you are supposed to be entertained — that’s why you have these weird sort of semi-comedic moments — but at the same time, they’re looking at in a too literal [a] form. I’m really just [portraying] what it’s like to be an Indonesian father and son, what that’s like, [and] also, what’s that like while dealing with something as weird as trying to be a musician?

And the melodramatic part of it, yes — what’s wrong with melodrama? I mean, what is wrong with that? That was a form of entertainment for the longest time and coming from being Asian-American [or] whatever motherland, if you wanna look at melodrama, look at daytime Korean dramas, or just Korean dramas in general, or Chinese dramas, or Taiwan dramas… that’s what we come from! Do we need to cater our films to your taste? And can you not at least critique in a way having considered where it comes from?

Jamojaya is not a story about an Asian-American, per se. They speak English, but it’s Indonesian. So what are the tenants of Indonesian entertainment and how [do] they tell stories? There’s a lot of folklore, [and] there’s a lot of Southeast Asian mysticism in their films, like Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives [and] Marlina the Murderer in Four Acts. On the flip side of it, it’s very broad. With that, I think, “I gotta get even more selfish with the stories I tell.” But also, if I’m gonna do that, I have to do it in a way that from the get-go, it’s sold and it already has a marketing machine behind it. Because frankly, like with Jamojaya, I’m like, “How many people will find outside the festival circuit?”

And maybe in the oeuvre of my work, that’s a pretty lofty term, but maybe in the library of what I build over decades, people revisit it and maybe appreciate what I’m trying to do as a whole [and] not as a singular notch in my belt. It’s like you’re playing a basketball game and it’s about the whole game, not one quarter or one play. Maybe over time, people will understand what it is that I’m trying to do.

Before I present every film, I state how I’m trying to bring empathy to the Asian-American community and Asians at large and make us understand that we’re more alike and different, [but] what can I do? Like, I can’t force you to like something, and that is my cross to bear [when I] make these kinds of films.

In terms of shooting in Korea or Europe, to answer your original question, it is that I don’t know, because I’m doing some real configuring and retooling on how I gotta approach this game, because as important as I do think that some of these films can be — these smaller films — if I can’t find an avenue for people to watch them — like, I’m not saying it needs to be Avatar — but who knows? Maybe they’re just not good enough.

And you can tell me, but, like, what it comes down to is maybe I’m tripping and they’re just not good enough and I just need to get better. And I do think I need to become a better writer, but at the current, I’m not even thinking about where I’m gonna shoot — I’m thinking about more macro [stuff].

ATL: Well, don’t put yourself down. I saw some of the reviews for Jamojaya beforehand, and I know you probably don’t want to hear about them, but I agree that some of them were focusing on the wrong things — maybe it’s a media literacy issue.

Chon: You know, the thing is, to your point, Andrew, that these critics drive business. If they are not understanding the film, that’s partly my fault. But it’s just like when people decide if they wanna watch a movie, these things matter in this day and age. Maybe not a long time ago, maybe it was more word of mouth, and when I talk to people who’ve watched the film, there are things there that I think are problematic about the film that I’ve gone back and I’m changing now because I think Sundance was almost like another workshop for my film — I’m okay with continuing to work [on it].

I said this at the premiere — I’m not trying to make perfect films. I’m trying to offer opinions and perspectives, [and] they’re not supposed to be perfect. They go, “Oh, this is far from a perfect film,” or, “This is not a perfect film.” [Well,] who’s trying to do perfect? It’s not gymnastics, where I’m trying to [be perfect] and every muscle needs to be in the right place. Art is supposed to be messy, but it does [need to] affect people discovering it.

Now, hopefully, over five films, people will see what I’m trying to do. But yes, to your point, I can’t say that they’re focusing on the wrong thing because that’s what matters to them, but I guess my job is to make it matter to them and that hasn’t yet really struck a chord in my work for the masses.

ATL: You just said you’re in the early stages of planning your next film and you’re not focusing on where you’re going to shoot or what you’re going to shoot, but I’m just curious what a more “mainstream” film looks like for you that isn’t Avengers or Avatar-sized?

Chon: Yes. And there’s nothing wrong with those films — I just wanna put that out there. I do truly believe that there’s a place for [blockbuster filmmaking] and I think it’s important. But I’m doing it right now. I’m making Chief of War with Jason Momoa. It’s about Pacific Islanders, specifically about Native Hawaiian/Indigenous Hawaiians… [there’s] a lot of drama in it, [as well as] culture, ancestry, [and] action.

I’m doing it now, and this is one of Apple’s biggest shows in terms of how much [has been] spent. They’ve already sort of advertised it — Timothée Chalamet did a thing for Apple — so it is much bigger, but still in line with my goal, which is to bring empathy to us, which is AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islanders). [The] PI part gets left out a lot of [times with] that equation. Beyond that, there [are] a few things I’m circling that are Asian-American-centric, [but] I don’t know.

I am going a little bit more through the studio system. [Maybe] there’s an IP tied to some of this stuff, so maybe that [will] help. I don’t know — I’m still trying to figure it out, [if I’m] being honest. And I’m as honest and as open of a book as can be. I’m not trying to say I’m sliced bread and invented that. I’ve still got a long way to go and I come from the acting world, so I’m still learning and growing and I’m gonna get better.

I don’t know these things that I’m approaching now, but I have a feeling. And I will say, at least [with] Miss Purple and Jamojaya, I didn’t approach it with this mindset of, “I’m trying to make this the biggest movie on Earth.” It was just [about] doing service to these communities. Southeast Asians are very underserved and there’s not a lot of interest outside of Southeast Asia… yet.

I love Southeast Asian cinema, but I wasn’t going for that with those [films]. [With] Blue Bayou, I would say I was, like, hoping for it to cross over a bit more. And what’s fucking crazy is, so many people saw that movie on airplanes and they’re like, “I don’t know why this film didn’t blow up,” or, “I don’t know why it wasn’t considered for awards,” or, “I don’t know why it wasn’t recognized more.” [I mean], the number of times that I’ve heard [things like] that… [and] no one was saying that about Gook, right?

So [the] number of times I’ve heard that… maybe part of it’s just the zeitgeist and luck — it did get released [during] COVID — but [maybe] there is something I am missing that’s within that process somewhere. Because I did feel like Blue Bayou was more universal. It was about family and it’s [set] in the South and they’re speaking with Southern [accents]… I don’t know how much more American you can get than that, you know?

Where’d you grow up?

ATL: I grew up in New York City, but then we moved to suburban Pennsylvania and went to school down South for a beat, so that’s why Blue Bayou hit home.

Chon: Yeah, exactly. So, my Grandma’s from suburban PA, totally like Amish [areas] — like an hour or two outta Lancaster. Maybe you’re not quite as far out as that, but I understand what that feels like for you to grow up in a neighborhood like that where people don’t quite know how to take you. But yeah, I felt it [Blue Bayou] was quite American, but I’m missing something and I’m trying to figure it out.

ATL: I wanted to ask you quickly about that film. You worked with Oscar winner Alicia Vikander on that film, and in the case of a lot of directors, once they get such a big name in their movie, they usually continue down that path, working with bigger stars on even bigger movies. But then you went and made Jamojaya, which is such an intimate film. Is there any particular reason you went with a smaller-scale project?

Chon: For me, the way I view filmmaking is not trying to get bigger and better. I truly think I’m trying to practice, and I’m trying to continue to make stuff, and I see a lot of filmmakers [who] make something that they really love, and then they wait four or five years to make something else. And that’s just not what I’m trying to do.

So, for Jamojaya, after I finished the television show Pachinko, [which] was in the [studio] system, I wanted to do something that was completely untethered and very artistic and trying to keep that sort of “indie spirit” [alive]. I really love independent films from the ’70s and sort of the ’90s, so there’s something different when you just have a crew, nobody’s getting paid a lot, everybody’s there because they wanna be there, and you’re all just kind of running in the same direction and you’re there because you want to tell that story.

I think after something like Pachinko or Blue Bayou, it seems like a natural trajectory to do a big studio film, but I think you start to get suffocated. And I think when you’re just starting out, there’s an idea of, like, “creative innocence,” and then you jump over to, like, experience, right? You jump over to this idea of becoming very experienced and knowing what you’re doing, knowing what you’re missing out on, and I think that to me — not always — but can sometimes become like creative death because you get too accustomed to the comforts of the machine.

So that’s why after Pachinko, I was like, “Okay, I got it. I gotta tough it out and do this,” and it was probably the hardest [thing to] film, just [being] on my toes and alive and also artistically grounded, I think.

ATL: On a related note regarding making the jump to a studio film, a friend of yours who I interviewed a couple of times, Sujata Day, jumped from Definition Please, which is a great film but a small one, and then she got tapped for a remake of American Pie. I know you just said you might not want to go make that sort of jump, but if you were given the chance to give your own spin on an American classic in your own way, maybe with an added Asian-American influence, is there anything that comes to mind?

Chon: No, not at the moment. I kind of just don’t think in that way because that, to me, feels very divisive and sort of like I’m just trying to repackage a product. I love Sujata, and I’m really happy for her that she’s doing that, but I don’t know if I’d find that enjoyable, just creatively, because it’s impossible, at least for me, for a property like that to not think about the original.

I think it’s perfect for her. I just think for myself, I would like to continue to work on originals — even in the television space. What I’m doing here [in New Zealand] is completely original. It’s not based [on] a previous work. I’m not saying that I wouldn’t, I think if there is a perfect property that I really love, [it’s not that] I wouldn’t, I just don’t have anything that gets me excited in that way right now.

ATL: One more question before we fully dive into Jamojaya… I’ve seen three of your four directorial efforts, and I’ve noticed that in the ones you’ve been in — Blue Bayou and Gook — your character gets beat up a couple of times, so I was just wondering if there is a specific reason for that, or if it mirrored real life at all?

Chon: Well, [in] Miss Purple as well, the girl gets beat up… I don’t know! I think there’s something just visceral about it. As you’ve seen, I don’t think my films are very cerebral — I think I make pretty “blue-collar” films. They’re about very normal people; they’re not really about people in academia or anything. They’re more about the 99 percent than the [top] 1 percent. So we’re just seeing very normal existence, and people are physical. I do think in 2023 that’s becoming less prevalent, but if you go to the hood, I think people are very physical, still.

ATL: Watching an interview you did with Rich Brian, who stars in Jamojaya, I learned about how you two had been working on this story for a long time, but tell me about the casting of Yayu A.W. Unru. He was so perfect in this movie and I don’t know that I’ve ever seen him in anything else before.

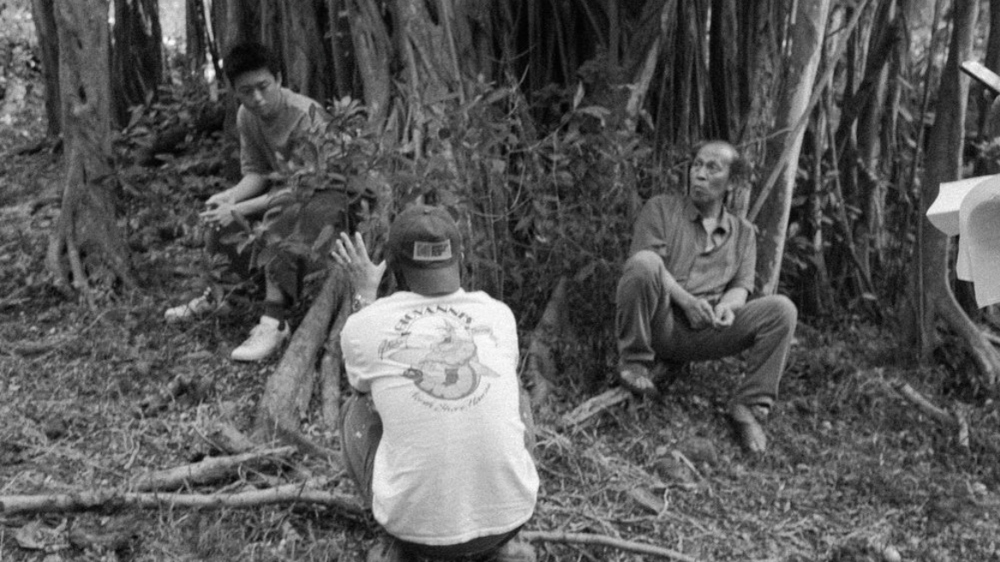

Chon: Originally, I had imagined the silhouette of father and son being a heavier man, and then the son being smaller and skinnier. But I had seen this film called Marlina the Murderer in Four Acts, and it went to Cannes, and Yayu had a small part in that. I saw a picture of Yayu on Google where he was just standing in front of this incense or smoke or something and his hair was a little disheveled and I figured [that] he had such a face and presence and I was like, “Okay, yeah. I’m almost positive [that] this guy’s perfect for the role.” So then I sought him out, we had a meeting and yeah, he was our guy.

ATL: You’ve talked extensively in other interviews about your working relationship with Rich Brian and how this film was a particularly long process, so I what was the best thing about collaborating with him?

Chon: I’d say he’s actually very thoughtful and he’s very — not precocious… because he’s not a little kid — but he’s very wise and a lot more conscientious than I thought. So working with him, you know, he really thinks through everything — a lot more than I thought he would — and I really appreciated that.

Yes, he’s very intentional and he didn’t wanna do things just because — he definitely doesn’t act like an early 20s kind of kid. That’s the thing that surprised me and I also appreciated a lot with him.

ATL: I know in real life that Rich Brian is a rapper-singer, so did he write the stuff that he performs in the movie?

Chon: That’s all him. He wrote original music for the film. So all [of] that music, he wrote, but he had the script and I said, ‘Hey, I want this song to feel like this. Here’s something comparable to what I’d like for it to sound like,’ and then he went off and would write the music.

ATL: Jamojaya begins with a fable — is this a real fable or is this something that you created?

Chon: Yeah, it’s a real fable. We found it in an Indonesian folktale storybook.

ATL: A tree is talked about in that fable and in the film, you found a tree that is just so perfect for it — was that something you guys stumbled across, or did you guys find that while location scouting?

Chon: [There are] two different trees [that] I’m using in two different locations, and I use a different banyan tree for the daytime, and then I use a different banyan tree for the nighttime.

ATL: A recurring theme throughout your films is parental relationships and how they vary. In Gook, there’s a kid with an absent mother who your character takes in, while Blue Bayou is about an adoptee, and your character has a young child. So, with parental figures being so present in your work, is that something you recognize when you’re writing stories, or is that just something that happened to recur in your films?

Chon: No, it’s very conscious. I explore a lot of themes of cultural baggage in my films. You know, Miss Purple is actually [about] siblings — it’s [a] brother and sister, but they’re also taking care of [their] dying father. But yes, it’s very conscious. It’s the idea of inheriting sort of past trauma, and that’s the same thing [with] Pachinko. It’s all about generational trauma that’s kind of inherited from generation to generation.

ATL: With the big argument scene in Jamojaya, was everything said scripted or did you give the actors freedom to go off-script and trust their emotions?

Chon: So, it’s scripted word-for-word, and then it was translated word-for-word into Indonesian. Then, when they got it (Yayu Unru and Rich Brian), they were like, ‘This is really hard to say,’ or, ‘This is a little too colloquial,’ or whatever. So then they changed it [to be] a little bit more natural [in terms of] the way they would say [it] each day, and then we rehearsed it for two months.

That’s why it feels so natural — is because it’s rehearsed. People think it’s improv, [but] it’s not. You can’t improvise that. Improvising that, you can’t make it that exact, and they wouldn’t be that quick on their feet to go boom, boom, back and forth, you know? You want to give that effect [though] — that’s the magic trick, right?

ATL: So then how many takes did it require to get the scene right?

Chon: I only did seven takes, but [we] got it on the third take. I could have stopped at the third take but I just wanted to see if they had anything else interesting, [so] I just did four more takes. But that’s because we rehearsed it, [so] they were ready.

ATL: I was reading your NBC essay, and if I’m not mistaken, you talked about wanting to now create films and kind of make your own path and do it your way. So you now have made five films, and in Jamojaya, creative freedom is a big concept. I know we just talked a lot about studio systems, but when watching the film, I kept thinking to myself that what Rich Brian’s character is going through kind of feels like you when his dad is telling him to not sell himself to the record label system. So can you talk to me a little bit about that story — is that at all supposed to be a metaphor for your own career?

Chon: Yeah [laughs]. In all honesty, 100 percent. You have to put yourself in everything to do, at least somewhat, because you want to care, you know? So yes, you picked up [on that correctly]. That is a metaphor for my career. But people don’t look into these films like that… they don’t give a fuck [laughs], you see what I mean? They’re not looking into it like you the way you are right now, and maybe because you thought about an identity a lot being an adoptee, like, maybe you’re a little more sensitive to it.

But most people don’t care to because they got busy lives. They [have] got a lot of shit they gotta watch — especially critics — but people really aren’t [looking into the films that deep], and I wanna create movies that make you think differently. Maybe I’m not doing a good enough job [of] making people think deeper. But, you know, it just seems like if I had slowed down the movie and made it two-and-a-half-hours [people would have appreciated it more] because the original version of two-hours-and-40-minutes is very much more of one of those tonal films, and I was very proud of that version of the film, but I just didn’t wanna bore people. And by the fourth time I’d watched it, I was getting sort of bored with it. But do I need to do that to get people to be like, “Oh, I should watch this with a more critical eye?” I don’t know, man. I probably don’t wanna do that, man. I’m just gonna keep doing what I think is right, you know?

ATL: I know that you also have a young child, right? How old is she?

Chon: She’s five.

ATL: I’m curious how being a father has impacted your films, specifically Jamojaya since it has that parent-child relationship, while a young daughter is also integral to the plot of Blue Bayou.

Chon: Yeah, [during] Gook [and] Man Up I didn’t have her yet. But for Blue Bayou, my wife was pregnant with her and [shooting] Miss Purple, the baby was already born. So everything after Blue Bayou, I had a kid.

So yes. If you watch my films, whatever’s going on in my life is very much [captured there]. [They’re] like a diary… a very expensive diary [smiles].

ATL: You’re currently filming Chief of War in New Zealand, as you said, so what’s the experience been like working with someone like Jason Momoa?

Chon: Jason is one of the kindest, giving [and most] generous people. He’s incredibly passionate, he’s incredibly involved. He wrote, produced [and is] starring in this project — so it’s his baby. He’s been trying to get this made for 15 years. But I’m here to service the Hawaiian people. I’m here to serve him and I’m in service — I’m trying not to be selfish about anything.

It’s not about me for this project, it’s about Pacific Islanders and getting something on-screen that’s significant, on [a] bigger scale, that will be marketed, that they can have that’s their own and [they can] be proud of. So I’m here to serve. And approaching it that way, I’m just trying my best to give them everything I got in my perspective, but also being sensitive to their culture.

Jamojaya premiered at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival and is still seeking distribution. Chief of War will likely premiere on Apple TV+ sometime next year.