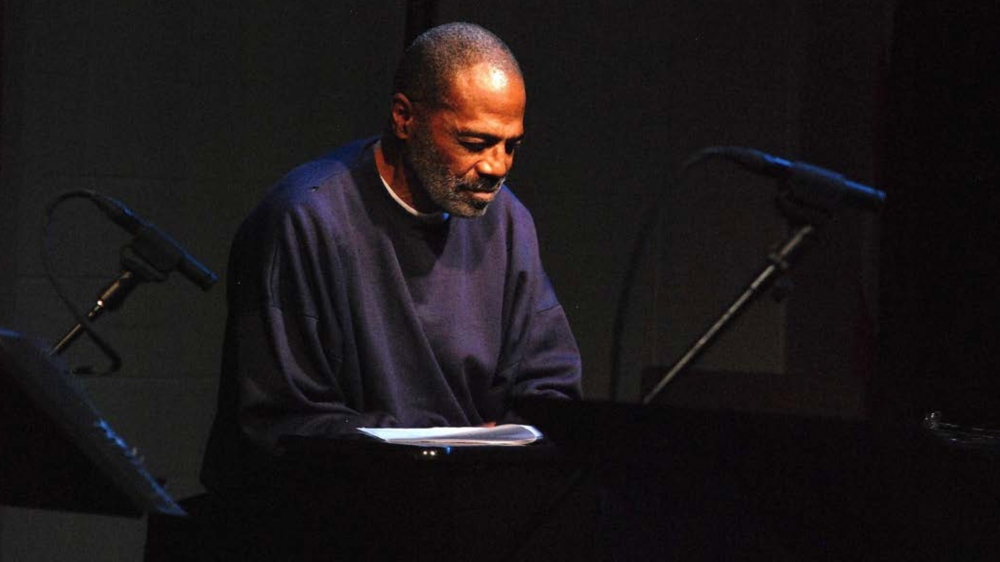

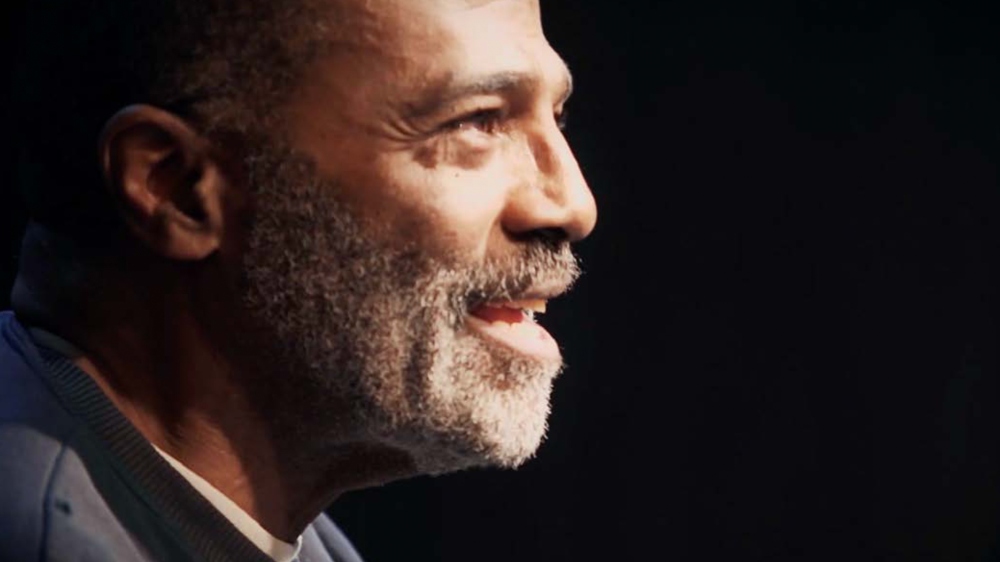

Reggie Austin spent 35 years behind bars after committing murder, a crime he never denied. He served as a model prisoner, performing music with fellow convicts, including famed jazz saxophonist Frank Morgan. Documentary filmmaker NC Heikin met Austin in 2012 while shooting footage for a Morgan tribute concert, and she became fascinated by Austin’s story.

He’d done his time, and yet he’d been turned down repeatedly for parole. Had he changed? Been rehabilitated? Did the prison system work, or did the privatization of prisons disincentivize them from releasing anyone? Heikin’s acclaimed documentary, Life & Life, explores all of those questions and more, as it follows Austin’s legal saga over the past decade, which has seen Austin try to reconnect with family and friends, find work, and reckon with the past. It hasn’t been easy for former Inmate #B57661.

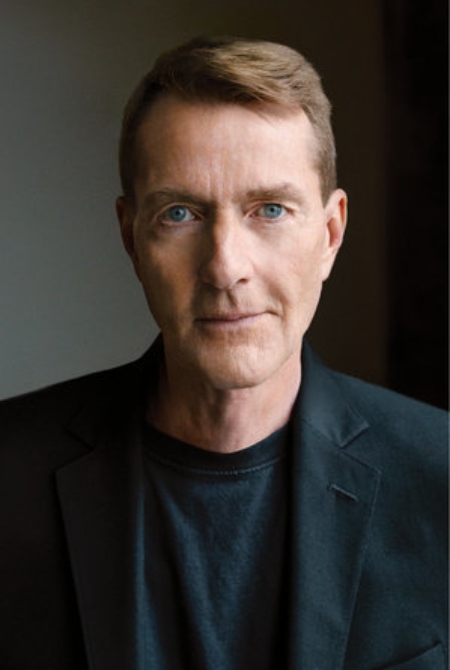

Austin’s story eventually caught the attention of famed British author Lee Child, who served as one of the documentary’s executive producers. Child is so passionate about Austin, the documentary, and all its implications that he even participated in a press day for Life & Life.

Below the Line caught up with Child via Zoom for an extensive conversation about why he chose to support Life & Life, which is now available on VOD and DVD, as well as his thoughts on prison reform and the criminal justice system, and what it has been like to let others (actors, writers, directors, readers, his own brother) interpret his best-known creation, the Jack Reacher book series.

Above the Line: How and why did you get involved with Life & Life?

Lee Child: How? It was easy. NC Heikin — who is the writer and director of the documentary — and I are good friends. We’ve been friends for possibly 20 years. She’s a documentary maker and I’m a novelist, therefore — for both of us — we live and breathe story. Whenever we bump into each other, which is quite often — either at a party or a dinner or something like that — we spend about seven seconds on polite small talk, “How are you? How’s the family?” Inevitably, one of us will say, “Hey, I heard about a guy who…” [and] then we’re off and running. We’re going through that story. We’re relishing it for its twists, turns, and unusual factors.

One night, she told me the story of Reggie Austin, who was just out of prison. I have a law degree from many decades ago. I also have a lifelong interest in criminal justice and jurisprudence, but every involvement that I’ve had prior to this has been about wrongful convictions. Somebody is in prison for a crime they did not commit, which is a horrific situation. It must be the worst possible feeling. We have to do something about it. We have to fix it. That’s where my attention has been up to now. That is a very simple, ethical, and moral dynamic. It is completely straightforward. Wrongful conviction is bad and it has to be stopped.

We know that, but the story of Reggie Austin was actually way more challenging because this was not a wrongful conviction. This was a righteous conviction. The man murdered somebody in his early 20s while he was high on drugs, [so it] then becomes a question of, “Do we believe in rehabilitation? Do we believe that people can turn their lives around and become better than they were?” That’s supposed to be part of the prison system.

You’re supposed to, obviously, sequester dangerous people away from the public. There’s obviously a component of punishment involved, but we also are supposed to rehabilitate these people, so — if possible — they can turn their lives around and come out of prison [as] useful members of society. But that is a liberal dream. We stake ourselves on that, but do we really believe it? When we’re lying in bed at night and staring up at the ceiling, do we believe it? Do we want an ex-con as a neighbor?

ATL: Those are all unsettling questions…

Child: That’s what this story explored, and it’s got a fabulous character in it — Reggie Austin himself. Yes, he did it. He murdered his girlfriend, but he immediately realized it. He didn’t contest the charges. He confessed. He pleaded guilty. He served his time, and during that period when he was in prison, he became a new person through the power of music — partly — but mostly through sheer determination. He put it behind him and became a better person. Then, the story morphed into the parole system. Does the parole system believe in rehabilitation? Does it recognize it? In Reggie Austin’s case, the answer was “no.” For decades, the guy was turned down for parole 12 times.

At that point, the story then evolved into yet another story, which was, “Who are these parole boards?” We were doing that part of the movie during the summer of George Floyd and Derek Chauvin, and we found out that most parole boards in most jurisdictions have a professional, plus two retired cops sitting as a threesome. We suddenly realized, “Wait a minute. The parole board could be two-thirds Derek Chauvin. It could be that bad. We need to look at that.” We need to make the parole system have absolute common sense and a hard line, but also be open to the possibility that people can get better. In this case, eventually, they did recognize that he was worth another chance.

ATL: How much did you have to believe in Austin yourself to put your name on this and to be involved?

Child: I would’ve been involved and had my name on it either way, because either way would’ve been an answer to the question, “Does rehabilitation happen?” The answer is either “yes” or “no.” If it had turned out to be “no,” then that is still a valuable contribution to the discussion. If we could say, “You know what? Actually, rehabilitation doesn’t work,” that is worth knowing.

As it turns out, rehabilitation does work, in many different cases… but are we ready to accept that? There was a third layer in the movie, which is when it’s incredibly difficult for somebody to transition from what has effectively been the majority of their life in prison to getting out into a world that they don’t recognize at all.

Think back 35 years. Suppose you had to be introduced to the world right now. Everything has changed in ways that make it very difficult to settle down. Do people need more help? Obviously, we’re not going to featherbed these people. We’re not going to use infinite resources, but do they need just a little bit more help than they’re getting?

Also, we need to ask a fairly blunt question. Are they only getting out now because they’re old, sick, and about to cost the prison system a lot of healthcare money? Which is a big, huge factor, and sadly — for Reggie Austin himself — that is what happened. Allegedly, there were dangerous fumes and asbestos in San Quentin. Now the guy is old and he has terrible lung problems. Have they dumped him out, not simply because they believe in rehabilitation, [but] have they dumped him out to save money? We need to explore these questions.

ATL: There’s the three-strikes issue. You can go to prison for the rest of your life for stealing a candy bar, if that’s your third crime. What are your thoughts on the light the movie sheds on that?

Child: You absolutely can, and I can understand the appeal to voters, that brisk, patient approach that voters have to people whose lives are completely unrecognizable to their own. “Well, we’ve given them two chances. If they screw up a third time, they deserve it.” I understand how a voter feels, but look at the damage it does. In Life & Life, we meet people who are lovely, but — as you said — they are effectively in jail for life for stealing a candy bar, kiting a check, or doing something that you or I would face no penalty for whatsoever. It’s upside down. It is a bad policy, and we need the maturity to say, “You know what? This has not worked. This is not right. We need to get rid of it.”

ATL: As a writer, what’s it like for you to witness and be part of a documentary as it comes to life?

Child: It’s incredibly awkward. As a fiction writer, if something isn’t going exactly right, you just change it. You make something else up. You can’t do that with a documentary. Documentaries have to be true, so you’ve got to work through the glitches in the story that are a little difficult. You’ve got to stick to it. You’ve got to tell the truth. For me, it was a whole new experience, not being able to just make it up and make it flow better, but the result shows a struggle that people need to see.

It shows that you can do a horrible thing when you’re in your early 20s, but then with enough will and determination — and in Reggie’s case, let’s be honest, the escape of music — you can channel something to turn your entire life around. You can become a different person. I guarantee that if anybody met Reggie Austin today, they would just love him.

ATL: How actively involved were you in creative decisions for Life & Life?

Child: I was very happy to trust NC. She’s an award-winning documentary filmmaker. Her instincts are great. She’s especially good with anything that involves music, so I was totally happy to step back and let her make almost all the decisions. I saw it all the way through. I was commenting. We were two storytellers kibitzing about, ‘What is the best way to transition to that?’ I had input, but not in a formal sense. There was no kind of formal approval. It was two friends trying to puzzle out, ‘We’ve got this great story. What is the best way of telling it?’

ATL: Let’s switch gears to Reacher. Your book series has sold a gazillion copies and inspired a couple of Tom Cruise movies as well as the current Amazon series starring Alan Ritchson, which has been a hit for the streamer. How different a beast, in your view, is television versus publishing?

Child: Television versus publishing? That is a great question because right at the very beginning, you have the complete opposite situation. If you have a great idea for a book, it is very unlikely to be bought by a publisher. The odds are against you. If it is bought by a publisher, then it is virtually certain that it will be published. It is almost automatic unless the world ends. If they buy a book, they are going to publish it. [In] Hollywood, film and television tend to work the exact opposite way around. They buy everything. Everything gets a deal…

ATL: …And then nothing happens.

Child: Yeah. The chances of it actually going ahead and being made are virtually zero, so it is completely the opposite situation. The other huge difference is that if a publisher publishes a book, even if they’ve paid quite a lot for it [and] even if it was expensive to produce, if that book fails completely — if it sells two copies, one to your mother and one to your dad — if it fails that badly, it will not bankrupt the publisher. The publisher can take that on the chin because they’re doing 1,000 or 2,000 books a year. Any individual title doesn’t make that much difference, whereas again, it’s completely the opposite in Hollywood.

Each individual operation might make five things a year, and if one of them bombs horrendously and all the investment is wasted, that could bankrupt them. That could give them a severe problem, and so the weight of expectation is so huge in Hollywood compared to publishing that it produces a whole different atmosphere.

ATL: How do you feel about your creation, this popular character Jack Reacher, appearing in films and TV shows that are outside your control, where writers and actors are interpreting and often dramatically changing your source material?

Child: It’s something that is not that much of a problem because very early on, your entire ambition is to have the character taken away from you. First of all, you want the reader to become fascinated [by] the character so that two or three books in, the reader essentially owns the character. Very early on, you get a sensation. This has happened to me a few times, but, you’re in a restaurant, and at the next table, they’re having a conversation about Reacher. “What did you think of the last book? Wasn’t that part great? What would Reacher do in this situation?” You’ve already given Reacher away at that point. Reacher belongs to those readers. Pretty early on in your career, the character is owned by the readers, collectively.

When it becomes a movie, the movie companies are only doing the same thing. They are thinking out loud. They are giving their opinion about what the character looks like [and] what the character would do. It’s the same thing. It is not a wrench, and it is not a surprise. In a way, it is actually what you’ve been aiming for since Day 1. You want other people to own that character, and so I’m completely relaxed about it. They can have him as long as they take it seriously. I’ve been extremely lucky that, with both the movies and the Amazon TV series.

The whole thing has been handled with enormous budgets, huge crews, and total professionalism. But they’re all Reacher fans. They’re doing it because they love the character and they want to do it, so his best interests are very well guarded. They’re not going to do anything that I wouldn’t want to happen. They’re not going to show him in a bad light. It’s a joy, to be honest, to feel you’ve created a character that can be owned by somebody else.

ATL: Speaking of somebody else, your younger brother Andrew is an author in his own right and co-wrote the most recent Reacher books with you. And he’s going eventually going to take over the book series, right? So you’ll literally be keeping the character in the family…

Child: Yeah, literally. That was a slightly different literary theory. I wondered how possible it was for another author to take over a character and reproduce it. Having read many attempts, I thought, “It’s about 95 percent possible.” But that little 5 percent margin…

ATL: …scares you?

Child: Right. That is a craziness in the author. That is the author’s individual madness that somehow gets on the page. I figured with my brother, because we share DNA [and] the [same] upbringing, and a lot of [similar] attitudes… I thought he would have the best possible chance of making that extra 5 percent because he’s as crazy as I am. And in the same way.

ATL: You worked at Granada Television, sitting at a mixing desk for nearly 20 years, and pursued writing after you got fired in 1995. You were known as James Grant back then. You published your first novel, Killing Floor, in 1997 under your Lee Child moniker. What do you think James Grant would make of the life and career that Lee Child has led?

Child: He would find it incomprehensible. I grew up a long time ago in post-war Britain, where horizons were incredibly narrow. The definition of success for me was something that [had] a very 1950s/1960s definition. My parents wanted me to be able to have a two-family house instead of a row house, and they wanted me to be able to have a two-year-old used car instead of a five-year-old used car, but that was about the limit of realistic expectations. If I could go back and whisper to that little lost and lonely kid all those years ago, I would say, “You’re not going to believe how this turns out.”

Life & Life is now available to buy or rent on DVD and all major VOD/digital platforms.