Swedish filmmaker Ruben Östlund has been making films for well over 20 years, but the real turning point came with his 2014 film Force Majeure, which won the Un Certain Regard Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival that year, as well many critics prizes for International/Foreign Language film. There would eventually be an English-language remake, the 2020 comedy Downhill, starring Will Ferrell and Julia Louis-Dreyfus, though it fully missed some of the intricacies of Östlund’s film.

In 2017, the director followed up with The Square, a look into the snobby world of fine art that introduced many Americans to Danish actor Claes Bang. As with Östlund’s previous films, The Square premiered at Cannes, but this time, it won the coveted Palme d’Or (Golden Palm). Many months later, it represented Sweden at the Oscars as one of five films in the “Foreign Language” category.

Triangle of Sadness looks to follow suit, having won Östlund his second Palme d’Or at Cannes this past May. There’s a misnomer that Triangle is Östlund’s English-language debut, but in fact, he has assembled an impressive and talented international cast, with only a few well-known faces here in the States, such as Woody Harrelson.

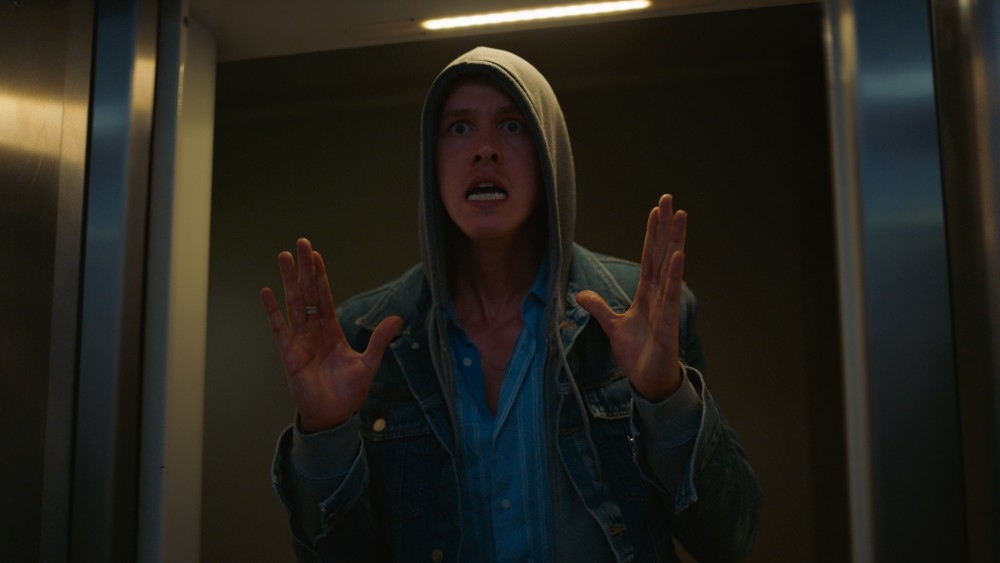

The movie revolves around a power couple of sorts — male model Carl (Harris Dickinson) and influencer Yaya (Charlbi Dean, who tragically died in August) — who decide to take a luxury cruise together even though they can’t even agree on who will pay for dinner. They’re joined by a group of wealthy vacationers and an absentee Captain (Harrelson). What happens on that yacht would put any relationship to the test, but none of the actors in Östlund’s talented ensemble could prepare themselves for the dark sociopolitical humor thrown at them over the course of production.

Above the Line spoke with Östlund over Zoom while he was relaxing in Spain with his wife in between festival appearances in the lead-up to the film’s North American release. We learned quite a bit about how he put his cast together… and what he put them through.

Note: It’s best to not really know too much about the movie in advance, so we’ll throw in a couple of spoiler warnings when appropriate.

Above the Line: What set you down the road to making Triangle of Sadness? Was it one particular idea or theme that got you started?

Ruben Östlund: There are two main things for me when it came to how this film started. First of all, I met my wife eight years ago, and she is a fashion photographer, so I got very curious about her industry. And then, later, when the #MeToo movement [began], I got very interested in the topic of beauty as a currency. I thought it was interesting when we were discussing the #MeToo movement, and we didn’t really discuss power and beauty as a currency, and the exchange of currencies between power and beauty and sexuality.

I thought it would be a great starting point to start the film in the fashion industry with the models, where it’s so obvious that they have their position in the fashion world because of their beauty. It’s an interesting aspect [how] you basically can be born everywhere in our society, and even if you don’t have education or money, beauty can make you climb in class society.

That was the starting point, to look at the two models, being in the fashion world, and then taking them to a luxury yacht. Look at the hierarchies on the luxury yacht, then take away all hierarchies in the third part, and then start to look at, “Okay, where do we end up?” And also, where do we end up when we are building a matriarchy instead? If we have a woman that is in the top position, will she abuse her power? Will she not abuse the power? There was a lack of that in the discussion, I felt, when it came to power structures, etc., etc. We made it into something that is very specifically male behavior, rather than a behavior that is connected with which position you have.

ATL: I also like the fact that you explain the title of your movie, Triangle of Sadness — those not in the fashion industry might be curious about what it means – in the first 10 minutes of the movie. It obviously works on other levels, but some filmmakers might hold that reveal until the very end of the movie.

Östlund: There was also something I got to know about when I met my wife. I thought it was so fun… because in Swedish, it’s called “trouble wrinkle.” So you get it from having a lot of troubles, but you can fix it with Botox in 15 minutes. It was just a fun contradiction. [chuckles]

ATL: Is it true that there was no actual working script? I was reading a few interviews with your cast, and they made it sound like you didn’t have a script with a beginning, middle, and end. Is that not so?

Östlund: It’s not 100 percent true. I would say, like, 95 percent of the film is completely scripted, but what I do when I have some setups where there’s a possibility to use improvisation instead is, I always do it at the beginning of the shooting day, in order to figure out, “Okay, are we really doing this in the best possible way?” But there’s always, like, “Okay, we start here, you have to go to that line, they have to go to that line, and then we go to the end.” They are [in] frame, where there are possibilities for improvisation. But for me, it’s very important to start every shooting day by really questioning the script [and] really saying, “Is this possible? Could this play out in this way if it happened? Do we believe in it?” When I put up the camera and I look at the monitor, I realize things that I couldn’t realize when I’m sitting and writing.

I have to use the shooting to improve the script and what we are shooting. Shooting for me can never be, “Okay, here’s the script. Shoot the script, now move on.” Shooting has to be, “How do we create the most spectacular version of the scene possible?” And then you have to use things that come up during the shooting and on the set.

I always do [it] like this. Always, the day before, at night, we sit and rehearse the scene that we’re going to do the next day, and then the day when we’re starting with it, then we have to be open. We have to think, “Does it work now when we’re looking at it?” And then I do up to Take 20, [and] it gets better and better and better, [and] then it often gets worse, and then you fight desperately to get up on the level of 20 again, and I say to the actors, “Take a 15-minute break.”

When they come back, I go, “Okay, everybody, five takes left.” And then I do a countdown, “Four takes left! Three takes left!” Really trying to build an intense feeling of… it’s now or never. The last five takes are very similar to each other, then we have sculpted the scene [and] we have decided everything to do. In Triangle of Sadness, in the last few takes, I gathered the whole film crew around the camera to look at the actors, and I also added a gong, like “BWONGGGG!!!” “Action!”

ATL: Did you have an actual, literal gong?

Östlund: Yeah, [it was] an actual gong. For me, shooting is about, “How do we capture a unique moment?” If everybody is so concentrated, if everybody is like, “Okay, we’re playing the World Cup final in soccer…” [Because] if we have that kind of intensity, then we can lift a scene up, and then we can bring it to editing.

ATL: Is that how you did The Square, too? I assume, due to the pandemic, that you couldn’t do table reads or rehearsals before getting everyone together to actually shoot the film. Is that how you’ve always done your movies?

Östlund: We [work with the] actors, [and it’s] very similar to when you’re doing a theater play. We read it through, I say what I believe we should work on, [and] what I think are the problems, and so on.

ATL: We should get more into the casting, because you managed to put together such an amazing group of actors. They not only have to be able to deliver your dialogue and help realize each of these characters, but they also have to be up for anything, considering what you put them through. Can you talk about casting Charlbi Dean, because it felt terrible to learn of her tragic death last month, especially after seeing how amazing she is in your movie and how much promise she had as an actress? Did you start by casting her and Harris Dickinson first, or did you secure a big star like Woody Harrelson first and then go from there?

Östlund: Yeah, it was Harris and Charlbi, but it took a long time before we found Charlbi. We were trying out a lot of actors for the Yaya part, and then a friend of my wife was saying, ‘You should really check out Charlbi Dean. She’s a model but she’s also acting.’ It was quite close to when we were supposed to start to film — we pushed it forward — so she came in quite late.

I was casting in Paris, London, Stockholm, Copenhagen, Manila, L.A., New York, [and] Berlin. I knew that I wanted to do an international cost. I was thinking, “Okay, if we do an international cast, let’s really make them fit together, play together, like an ensemble — give each other energy, be dynamic. And let’s not fill it with stars. Let’s really like the different characters and make a rich palette of expressions.” I had, as a goal, [to] create a Real Madrid of f*cking eight great players [who are] going to give us a great performance. So that was basically the goal.

ATL: I was really amazed by Dolly De Leon. I wasn’t familiar with her, but apparently, she’s a prominent stage and screen actor in the Philippines. I had no idea there was such a great acting pool there, so how did you find her for this important role? (SPOILER WARNING #1)

Östlund: We went to Manila and did casting with a lot of actors. She did a very impressive improvisation around when she’s taking control around the fire. She’s a really great actress. She understands how to control the group, and she is a high-status person. Dolly De Leon is a high-status person, and she knew how to do that in a believable way. It was a very critical point in the film, that you believe that someone [who] had been on the boat [could] actually take control over the group without any violence, really.

When we were shooting, I almost [could] feel it, and this is just my belief — you have to ask Dolly if she thinks so — that there is a certain kind of aggression that is there in the base. If you look at who people are working with, with the shipping companies and the shipping industry, and so on, everybody that is on the lowest payroll is [from] the Philippines. Of course, you get angry because of this. She, of course, is aware of this fact, and she could also enjoy taking control. It meant something more to her than just doing it in the part — that’s at least how I felt it.

ATL: I feel like there are a lot of people like that in New York, too — basically, essential workers who aren’t treated very well, and you wonder what they might do if the shoe was on the other foot, so to speak.

Östlund: It was interesting, because I had a screening in Paris, and afterward, one gentleman was very upset, and it turns out, he’s a billionaire. He was saying, ‘It’s not so simple. It’s not so simple.’ I’m trying to ask him, ‘What is it? Can you be more specific? I don’t understand what you mean.’ ‘No, no, no, if you don’t understand that, I can’t tell you anymore.’ ‘Are you talking about Claus? I can just assume that you’re talking about Claus.’

I’m sorry. This is exactly how simple it is. There’s a certain way the conservative right-wingers, in my opinion, they want to say, “Oh, this problem is very complicated.” It’s not complicated! It’s about how we are sharing the wealth in the world. That’s what it’s about, so we can say that it’s okay to exploit workers. It’s okay to do this, because I took the initiative, blah, blah, blah. But if you don’t treat people in a fair way, that’s just how simple it is. Actually, we meet Claus outside every day when we go out on the street. As soon as we are thinking as individuals, we should take care of this. It’s not possible. We have to take care of it on a societal level. We have to stop bullshitting, and pay taxes.

ATL: Did you film on an actual boat, or did you build the boat interiors on a stage and then do the last part outside somewhere?

Östlund: We built the dining room, part of the command bridge, two corridors, [and] we built in a studio. And then we could rock [it] on a gimbal like this. We also shot on a real yacht called Christina O, which is Onassis. The whole Western elite was spending time on that yacht — [John F.] Kennedy, Marilyn Monroe, Maria Callas, Churchill — everyone was on that yacht in the ’70s, so it became an interesting symbolic value to blow it up.

SPOILER WARNING #2!

ATL: I don’t know if you’ve seen the famous vomiting scene in Stand By Me, but you may have topped it in this movie.

Östlund: I hope so because I was like, ‘Wasn’t that a children’s movie?’ It’s a great movie. I loved it when I saw it, but it was a long time [ago when] I saw it. I think that Monty Python was probably the one that I was like, ‘Okay, we have to top that one.’

ATL: You mean Mr. Creosote, the guy who eats everything and eventually explodes from Meaning of Life?

Östlund: Yes, it’s Meaning of Life, of course. I also decided quite quickly that, “Okay, if we’re going to have a storm, and people are going to get seasick, I have to go further than the audience expects, because otherwise, it’s not going to really become something.” But now I think, “Did I go too far, because this is the only thing that people want to talk about afterward?” [laughs]

ATL: I’m curious whether you consider Triangle of Sadness to be a comedy. There’s a lot of really pointed sociopolitical commentary about the world, and there’s a lot about it that makes you laugh, but then you think, “Wait a second. Should I be laughing at this?” I know Scandinavians have a very specific type of humor that’s quite a bit different than our sense of humor here in America.

Östlund: What I’ve always enjoyed when I go to the cinema… is a director [who] is challenging me a little bit. Also, I love scenes where there’s one moment when you actually laugh, and the next moment, it can be a little bit too harsh or horrible in some way. It’s balancing between these two things, and it makes it insecure for the audience to watch a little bit.

I remember my early inspirations when I was in film school, and I saw Michael Haneke‘s Code Unknown. I felt like he had such strong suspense, because I didn’t feel 100 percent sure [how to feel], as an audience [member]. It’s important to me that the film shouldn’t be too easily placed as an audience. If the audience knows, “It’s a comedy, okay, let’s watch,” [then] I want the audience to be on their toes, and I want them to never expect what will come around the next corner. That’s why I also think it’s definitely not just a comedy, and it’s definitely not a dark drama only.

My dream is that one day, you would [simply] say, “It’s a Ruben Östlund film.”

Triangle of Sadness is now playing in select theaters, courtesy of NEON.